Christopher Plein, Ph.D. West Virginia University

As a social scientist, I am drawn to the facts and figures that describe the world around us. A recent visit to the Department of Defense’s DMDC website proved this to me yet again. As is common in the military, the DMDC serves as a shorthand acronym – in this case for the Defense Manpower Data Center. We have discussed DMDC resources in previous blogs. Because of the work that I do the OneOp caregiving concentration, I am especially interested in trends and patterns in the active duty component of the military.

It is helpful to return data sources on a regular basis. The “Number of Military and DoD Appropriated Fund (APF) Civilian Personnel Permanently Assigned” quarterly report is especially helpful. The March 2018 report provides important breakdown information between activity duty and civilian assignments. It can be downloaded in excel from DMDC’s Personnel, Workforce Reports & Publications website. The charts and discussion that follows in this blog are drawn from the March 2018 report.

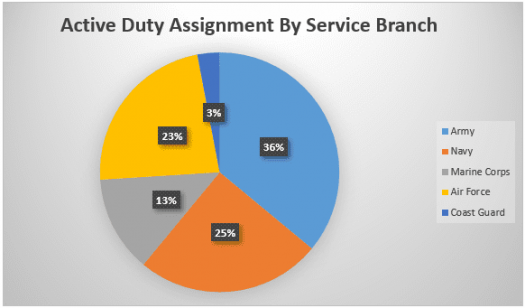

As of March 2018, the overall active duty military members stood at approximately 1.33 million. Of these approximately 1.16 are assigned in the United States. Of these, 36 percent or 416,667 are with the Army. As the pie chart below illustrates, the distribution is followed next in order by the Navy (285,141), the Air Force (266,167), the Marine Corps (153,107), and the Coast Guard (39,960).

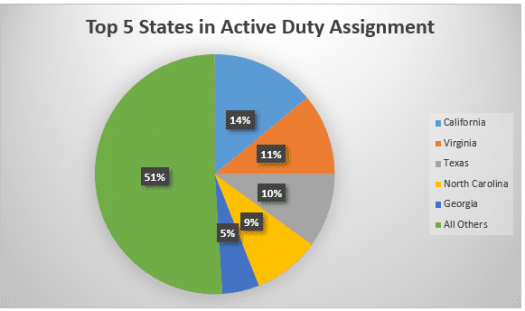

Active duty personnel stationed in every state. California has the most active duty members, totaling some 157,583 while Vermont has the fewest at 165. Along with California, the top five states for active duty military assignment are Virginia (123,341), Texas (119,272), North Carolina (100,606) and Georgia (63,645). Essentially, 1 out of 2 activity duty military personnel are stationed in one of these five states. The chart below illustrates this distribution.

The numbers tell us even more. Some service branches tend to concentrate in a few states. Almost two-thirds active duty Marine Corps personnel can be found in two states – California (58,101) and North Carolina (42,837). A similar pattern holds for the United States Navy. Half of all assigned personnel can be found in Virginia (73,368) or California (70,086). Next in line is Florida with 25,458. Together these three states account almost 60 percent of assignment locations.

In contrast, both the Army and U.S. Air Force tend to be more geographically dispersed. In the Army high concentrations of assignment include Texas (71,898), Georgia (46,939), North Carolina (44,989), Kentucky (31,608), Washington State (26,844) and Colorado (25,937). Together these 6 states comprise about 60 percent of Army active duty assignment. In the Air Force concentrations of active duty assignments can be found in Texas (37,089) Florida (23,118), California (17,988), Virginia (12,109), New Mexico (11,974), Arizona (10,066), Nevada (9,891), Georgia (9,331), and Colorado (8,599). Together these 9 states make up about 53 percent of assignment locations.

These data tell us something about the distribution of the active duty military across the country, but they also raise some interesting questions that can help guide efforts to work with and support military families. As we have discussed in previous blogs, active duty military personnel and their families are deeply intertwined in their communities. We know that frequent transfers can create unique challenges to getting access to services and connecting to community-based resources. With this in mind, consider some of the following:

- What is happening in those states with high military populations to ensure that families are able to connect to needed resources? How is this reflected in terms of policies and programs relating to healthcare and education? How does this play out more informally through the efforts of community-based service providers?

- Conversely, what challenges emerge for military families in states where there are few active duty military assignments? Are policies and programs sensitive to the situations of these families? Are community-based service providers aware of the needs of military families?

- Since each of the service branches have considerable discretion in structuring and operating family support activities, do assignment patterns focusing on a few states influence programs and practices – and vice versa?

These are questions that are worth considering. Much of the work of the OneOp concentrates on how to best understand context and environment in order to better connect military families to resources at the community level and beyond. By returning to the data, we are able to identify both challenges and opportunities that relate to our work.