By: Jennifer Rea, PhD

“War holds many ironies and among them is the liberating effect upon women”

– Doris Weatherford, Women’s History Scholar

American women have served in the military for a long time and with much distinction. Their service (although prohibited at the time) first began during the Revolutionary War (1775-1783); some wives and mothers followed their husbands or sons off to war (King & DiNitto, 2019). These women assisted as civilian laundresses, seamstresses, cooks, and nurses. To serve as soldiers, some women disguised themselves as men (King & DiNitto, 2019).  One woman, Deborah Sampson, served for over a year (1782-1783) in General Washington’s army disguised as a man. However, after being wounded, her gender was discovered, and Deborah was honorably discharged (Michals, 2015).

One woman, Deborah Sampson, served for over a year (1782-1783) in General Washington’s army disguised as a man. However, after being wounded, her gender was discovered, and Deborah was honorably discharged (Michals, 2015).

Throughout this time, women served with, not in, the Armed Forces. “That is, even though they may have been paid (or not paid) for the duties they performed, they did not hold military rank and were thus attached to, not a part of the Armed Forces” (Devilbiss, 1990,p.1).

In both the Civil War (1861-1865) and Spanish-American War (1898), women continued to serve as civilians in needed positions, including administrators, spies and cooks of battlefield hospitals (Women’s Memorial, 2017). By 1861, Congress authorized women to serve as paid contract nurses,  but the pay women received was half that of what male nurses received (King & DiNitto, 2019). This sparked the formation of the Army Nurse Corps (1901) and the Navy Nurse Corps (1908); each were the first all-female Reserve Corps (Gavin, 2006). While this was a significant leap forward, these women were only “contract nurses” that did not receive equal pay, military rank, medical or retirement benefits (King & DiNitto, 2019).

but the pay women received was half that of what male nurses received (King & DiNitto, 2019). This sparked the formation of the Army Nurse Corps (1901) and the Navy Nurse Corps (1908); each were the first all-female Reserve Corps (Gavin, 2006). While this was a significant leap forward, these women were only “contract nurses” that did not receive equal pay, military rank, medical or retirement benefits (King & DiNitto, 2019).

It wasn’t until the last two years of World War I (WWI, 1917-1918), that women were allowed to join the military (History.org, 2008). More than 35,000 women served in the military during WWI (Taylor, 2018). The service of these women helped propel the passage of the 19th Amendment (June 4, 1919), guaranteeing women the right to vote (Library of Congress, 2019).

During World War II (1941-1945), more than 400,000 women served at  home and abroad as mechanics, ambulance drivers, pilots, administrators, nurses, and in other non-combat roles (Taylor, 2018). Due to the large influx of women, the Armed Forces created new organizations to manage their service within the larger, male-dominated military (Taylor, 2018). The first organization created was the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC, 1941),creating over 400 jobs for women to work primarily in baking, clerical, driving and medical fields (Gavin, 2006).

home and abroad as mechanics, ambulance drivers, pilots, administrators, nurses, and in other non-combat roles (Taylor, 2018). Due to the large influx of women, the Armed Forces created new organizations to manage their service within the larger, male-dominated military (Taylor, 2018). The first organization created was the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC, 1941),creating over 400 jobs for women to work primarily in baking, clerical, driving and medical fields (Gavin, 2006).

The creation of WAAC spurred each branch of the Armed Forces to form their own all-female reserve units. The Navy established WAVES (Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service, 1942), the U.S. Coast Guard Women’s Reserve created SPARs (Semper Paratus- Always Ready, 1942), and the Marine Corps Women’s Reserve established Women in the Marines (1943).

(Pictured left to right: Navy Reserve Lieutenant Commander Mildred H. McAfee, the first female commissioned officer of the U.S. Navy and the first director of WAVES; Coast Guard Reserve Lieutenant Commander Dorothy C. Stratton, the first Director of SPARS; and Marine Corps Reserve Colonel Ruth Cheney Streeter, the first Director of Women Marine Reservists)

Also, in 1943, the Women Air Force Service Pilots (WASP) program was  created—a group of civilian women military flight duties. WASP defied cultural norms and traditional gender roles in both the military and the field of aviation (Stamberg, 2010).

created—a group of civilian women military flight duties. WASP defied cultural norms and traditional gender roles in both the military and the field of aviation (Stamberg, 2010).

In 1947, the Army-Navy Nurse Act was established, granting permanent commissioned officer status to women in the Army Nurse Corps and Women’s Medical Specialist Corps (King & DiNitto, 2019). In the year following (1948), the Women’s Armed Services Integration Act granted non-nurse women permanent status in all branches of the regular and reserve Armed Forces; entitling them to full military authority and veteran benefits (Kemble, 2017).

During both the Korean War (1950-1953) and Vietnam War (1955-1975), women continued to voluntarily serve. At the time, 500 female Army nurses served in combat zones, and many female Navy nurses served on hospital ships (Library of Congress, 2019).

Towards the end of the Vietnam War, the military draft ended and an all-volunteer military was formed (1973). Slowly, the doors began opening for women as more opportunities were created for those seeking a career in  military service. Possibly one of the greatest historical moments was in 1976, when the first females were admitted to service academies, including the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, the U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis, and the Air Force Academy in Colorado (Women’s Memorial, 2017). In that same year, the first female Army ROTC (Reserve Officers Training Program) cadets graduated from South Dakota State University. With more women entering careers in the military, Congress disbanded the Women’s Army Corps (formerly WAAC) in favor of truly integrating the military. Then, in 1977, basic training became integrated (Army.mil, 2019).

military service. Possibly one of the greatest historical moments was in 1976, when the first females were admitted to service academies, including the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, the U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis, and the Air Force Academy in Colorado (Women’s Memorial, 2017). In that same year, the first female Army ROTC (Reserve Officers Training Program) cadets graduated from South Dakota State University. With more women entering careers in the military, Congress disbanded the Women’s Army Corps (formerly WAAC) in favor of truly integrating the military. Then, in 1977, basic training became integrated (Army.mil, 2019).

These significant strides created more equality for women and encouraged changes for servicewomen and their families. On June 30, 1975, the Defense Secretary directed the elimination of involuntary discharge of military women because of pregnancy and parenthood (Army.mil, 2019). This was also the first time in history that some pregnant women voluntarily continued to serve (King & DiNitto, 2019).

After the Vietnam War, women in the military were sent around the globe in co-gender crews that responded to regional conflicts, natural disasters, and humanitarian crises. During this time, many women found themselves in active combat zones. This resulted in the 1988 “Risk Rule,” which found that women could not be placed in areas that were considered to be of “high risk” (Kemble, 2017).

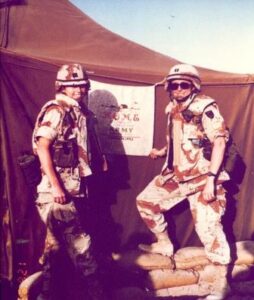

Despite this ruling, more than 24,000 women were deployed to hostile  combat zones, serving in the Persian Gulf War (also known as Operation Desert Shield/Desert Storm, 1991-1992) (History.org, 2008). This was the first time in history that women were authorized to fly in combat missions (1991), serve on combat ships (1993), and be placed in command of military units (1993) (Women’s Memorial, 2017). “Understanding that it was best for all members of the team to be well equipped and prepared for combat zones, in 1994 Congress overturned the ‘Risk Rule,’ making it legal for women to enter hostile combat zones as long as they didn’t engage in direct combat” (Kemble, 2017).

combat zones, serving in the Persian Gulf War (also known as Operation Desert Shield/Desert Storm, 1991-1992) (History.org, 2008). This was the first time in history that women were authorized to fly in combat missions (1991), serve on combat ships (1993), and be placed in command of military units (1993) (Women’s Memorial, 2017). “Understanding that it was best for all members of the team to be well equipped and prepared for combat zones, in 1994 Congress overturned the ‘Risk Rule,’ making it legal for women to enter hostile combat zones as long as they didn’t engage in direct combat” (Kemble, 2017).

Between 1992 and 1999, the U.S. military responded to regional conflicts, natural disasters, and humanitarian crises all over the world (Army.mil, 2019). As part of the missions in Somalia, Haiti, Bosnia and Kosovo, women were trained for various tasks, including coping with food riots, terrorist attacks, ethnic and clan conflicts, and peacekeeping (King & DiNitto, 2019).

In response to the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, many servicewomen deployed in aid of the wars in Iraq (Operation Iraqi Freedom, 2003-2011; Operation New Dawn, 2010-2011) and the war in Afghanistan (Operation Enduring Freedom, 2001-2014). With the Global War on Terror campaign, there was a rapid expansion of jobs and change in roles for women.

In 2010, the Army established Female Engagement Teams (FET) and Combat Support Teams (CST), which were comprised of all-female teams performing duties such as intelligence gathering, relationship building, and humanitarian efforts (Army.mil, 2019). The primary task of these teams was to engage female populations where such engagement was not possible by male service members.

In 2010, the Army established Female Engagement Teams (FET) and Combat Support Teams (CST), which were comprised of all-female teams performing duties such as intelligence gathering, relationship building, and humanitarian efforts (Army.mil, 2019). The primary task of these teams was to engage female populations where such engagement was not possible by male service members.

The success of these missions and the fight for equality made so that in January 2013, Secretary of Defense Leon E. Panetta announced that all military positions were opened to women as long as they could meet the necessary qualifications (Kemble, 2017). Just three years later, in January of 2016, women were able to choose any military occupational specialty, including ground combat units, as long as they qualified and met specific standards (King & DiNitto, 2019).

Today, approximately 2.5 million women serve in the U.S. Armed Forces, according to the Service Women’s Action Network. Women continue to make their mark and show their determination as they volunteer to serve in the U.S. military. Currently, there are approximately 800 women serving in combat-related roles (Myers, 2018). Women also serve in many other roles such as operating equipment, as well as maintaining and repairing it; supervising junior personnel, law, atmospheric science, meteorology, biological science, and social science to name just a few (McKay, 2019).

Women who serve in the military are vital to U.S. national security and it is imperative that the military continues to learn from the past to lay the groundwork for a future of a more integrated military service that supports female service members throughout their military journeys.

Women who serve in the military are vital to U.S. national security and it is imperative that the military continues to learn from the past to lay the groundwork for a future of a more integrated military service that supports female service members throughout their military journeys.

References

1. Army.mil (2019). Women in the Army. Retrieved from https://www.army.mil/women/history/

2. Devilbiss, M. C. (1990). Women and Military Service: A History, Analysis, and Overview of Key Issues. DIANE Publishing.

3. Gavin, L. (2006). American women in World War I: They also served. University Press of Colorado.

4. History.org (2008). Time Line: Women in the U.S. Military. Retrieved from https://www.history.org/history/teaching/enewsletter/volume7/images/nov/women_military_timeline.pdf

5. Kemble, H. (2017). Heroines in Arms: Women of the American Military. Retrieved from https://womensmuseum.wordpress.com/2017/07/05/heroines-in-arms-women-of-the-american-military/

6. King, E. L. & DiNitto, D. M. (2019). Historical policies affecting women’s military and family roles. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 39(5/6), 427-446. doi:10.1108/IJSSP-01-2019-0010

7. Library of Congress. (2019, June 4). Congress Approves Nineteenth Amendment. Retrieved from https://www.loc.gov/item/today-in-history/june-04/

8. Michals, D. (2015). Deborah Sampson. Retrieved from https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/deborah-sampson

9. McKay, D. R. (2019, June 25). Careers for Women in the Military. Retrieved from https://www.thebalancecareers.com/women-in-the-military-4177666

10. Myers, M. (2018, October 9). Almost 800 Women are Serving in Previously Closed Army Combat Jobs. This is How They’re Faring. Retrieved from https://www.armytimes.com/news/your-army/2018/10/09/almost-800-women-are-serving-in-previously-closed-army-combat-jobs-this-is-how-theyre-faring/

11. Stamberg, S. (2010). Female WWII Pilots: The Original Fly Girls. Retrieved from https://www.npr.org/2010/03/09/123773525/female-wwii-pilots-the-original-fly-girls

12. Taylor, W. A. (2018). From WACs to Rangers: Women in the US Military since World War II. Marine Corps University Press Quantico United States.

13. Women’s Memorial. (2017). Highlights in the History of Military Women. Retrieved from https://www.womensmemorial.org/timeline

Writers Biography

Jenny Rea, Ph.D., is a military spouse and mom of four kiddos under six years. Jenny consults with OneOp and is an Assistant Professor of Practice in the Department of Human Services and Director of the Certificate in Military Families at the University of Arizona.

Jenny Rea, Ph.D., is a military spouse and mom of four kiddos under six years. Jenny consults with OneOp and is an Assistant Professor of Practice in the Department of Human Services and Director of the Certificate in Military Families at the University of Arizona.

Photo source: Adobe stock