By: Bari Sobelson, MS, LMFT & David Lee Sexton, Jr.

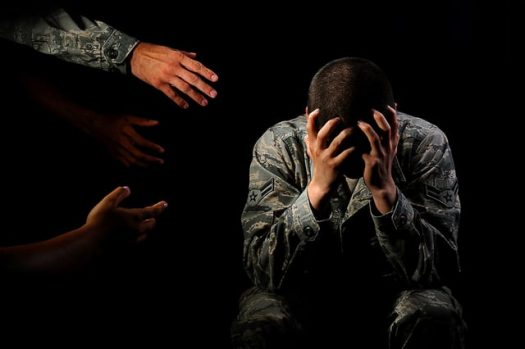

Family and friends can be important influences in helping someone get treatment for mental health issues. Reaching out and letting them know you are there to help them is the first step. (U.S. Air Force illustration by Airman 1st Class Devin N. Boyer/Released)

Beyond Staying Strong by Seeking Help

On Thursday, April 19, 2018, Dr. Thomas Britt from Clemson University facilitated a webinar capturing the barriers and facilitators to military mental health treatment-seeking.

Dr. Britt started the webinar off with this: “It probably doesn’t take much to convince everyone that we have a situation here, where because of the nature of their work, military personnel get exposed to traumatic events and these traumatic events have been linked to the experience of mental health problems… at the same time, there are effective mental health treatments that are available to service members if they would go and get them. If they would go and get them early, there’s evidence to suggest that their problems would not get severe and interfere with their family life as well as their personal life.”

Why Don’t Service Members Seek Help?

Stigma! Stigma is the primary factor that has frequently been discussed as a deterrent to treatment seeking. Stigma surrounding mental health is problematic even for civilians, but for military service members who are expected to endure hardships most of us can’t even imagine, stigma can be even more burdensome.

Why Dr. Britt Got Interested

Dr. Britt became interested in mental health treatment seeking among service members and stigma due to an experience he had in 1996. During that time, the military wanted to screen service members coming back from the peacekeeping deployment to Bosnia by assessing their medical and psychological health and proactively intervening to address any problems that were emerging before they became severe.

When involved in the screening, service members completed medical questionnaires and then they completed mental health questionnaires. If they screened positive for a medical issue, they stood in one line to be seen by a medical provider and if they screened positive for a mental health issue, they stood in another line to be treated by a behavioral health provider. The service members soon figured out which line was associated with mental health and which one was associated with medical problems. There were jokes about soldiers having to go to the “loony line” and it was common to hear “I’m gonna have to take your weapon before you talk to the person”. This conveyed to Dr. Britt a visible stigma associated with having a mental health problem which led him to the initial study.

This led Britt to a startling revelation, but one that is seen over and over again: those service members MOST in need of help are those who perceive the highest level of stigma associated with getting mental health treatment.

High risk occupations like the military have a culture that deters getting help for mental health problems. Resilience is highlighted over and over in the military and there’s an expectation that soldiers will show resilience. Any sign that you’re not resilient is perceived as a mark on your record.

Insights from the webinar:

- Stigma prevents military members from receiving needed mental health services. “The association of stigma as a determinant of why military personnel don’t get treatment has, at times, proved elusive to document. But, certainly, that is the primary factor that has frequently been discussed as a deterrent to treatment seeking.” Britt shares terminologies associated with the stigma of getting help: Public Stigma, Self- Stigma, and Label Avoidance. In addition, it is important to note the significance of having support from family, leaders, and peers when seeking mental health treatment.

- Need for increased visibility of mental health professionals. This was a recommendation that came out across the different studies that Britt and colleagues have conducted. Greater visibility and accessibility of behavioral health providers may help to encourage reaching out for help.

- Ways in which unit leaders can be trained which may increase support of their members. Unit leaders are very influential in a service members inclination to get help if they have a problem. If the leader is supportive, then service members are much more likely to get treatment than if the leader views treatment as a waste of time.

- Video training resources are available. Dr. Britt shared information about the unit training they developed in order to increase the support that soldiers would show towards fellow unit members who needed mental health treatment. They knew they needed to target the smallest unit in which the soldier was embedded. The training delivered to squads was designed based on the qualitative and quantitative research described earlier in the webinar. The training developed is heavily populated with the unique organizational culture of the military. Areas of training and the format of the training are described on slide 25 of the presentation.

- The impact of soldiers reporting positive experiences in seeking assistance and the positive impact of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). Dr. Britt discusses research on civilian employees which found that CBT was related to decreased time away from work to acquire mental health treatment. This has good implications for soldiers who may feel that they are letting down their unit by being away to receive treatment. Furthermore, exposure to positive experiences with CBT may work to lessen the stigma associated with mental health treatment seeking.

- Research now shows that getting help early on will improve resilience. Some may get the idea that if they require and seek out mental health treatment, it means they have failed to be resilient. Consider this counterargument: if military personnel get treatment early when the problems are not severe, then getting early mental health treatment can be seen as a contributor to resilience rather than a failure to be resilient. One of the problems is that the culture we’ve talked about highlights mental health treatment as a last resort. If it could be emphasized that the early treatment for these problems is a contributor to resilience and if leaders create a climate within the unit where this is encouraged, then perhaps we can begin to view mental health treatment as an asset rather than an indicator of failure.

- Misconceptions military members have about mental health medications, and how participating in therapy will influence their ability to remain in the military. In each focus group, there was an example of one of the NCOs who basically said that one of their soldiers went to Behavioral Health, got put on medication, and came back as a “zombie”. That one highly visible case study can create a whole perception within the unit that psychotropic medication is addictive and it can harm your performance. Misinformation can be put within the units.

- The military’s efforts to improve mental health care and reduce stigma. While there is still progress to be made, it is important to note that leadership in the military is working hard to combat stigma associated with mental health treatment seeking.