Mexico-U.S. border at Tijuana. © Tomas Castelazo, www.tomascastelazo.com / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 4.0

In our early childhood mental health program at the University of Minnesota, one of the first things I teach new trainees is to screen for trauma. We ask about abuse and neglect, natural disasters, and witnessing community or domestic violence.And we ask about separations. Separation even for a parent’s business trip, a perfectly innocuous event, can impact a young child. We know that even after children are reunited with parents, an unexpected separation can continue to have a lasting impact.

So, when it became known that migrant and refugee children were being separated from their caregivers at the U.S.-Mexico borders, it was no surprise to see pediatricians, mental health professionals and educators speaking out against the practice. Developmental science experts have warned of the negative impact of this stressful and traumatic experience on young children’s emotional and behavioral functioning, as well as their long-term stress biology and brain development.

As mental health and healthcare professionals, educators and caregivers, we adopt trauma-informed care practices and consider the impact of adverse childhood experiences (or ACEs). We ask not “what’s wrong” with this child, but “what happened” to this child. In the case of border separations, the ‘what happened’ is obvious. What is less obvious is that many of the children arriving at the border have experienced at minimum a stressful travel experience. Those seeking asylum may also be fleeing from gang violence, domestic violence, or other atrocities. Decades of developmental science research tell us that cumulative risk is the crux of where emotional and behavioral problems can begin; the more adverse events a child experiences, the greater the risk for long-term academic, social, and emotional concerns. The child’s cumulative risk or ACE score prior to arriving at the border was already greater than 1, putting them at a high level of risk for long-term concerns.

After reunification, children are left to piece together the explanation for why the separation happened. This lack of security can manifest in a host of mental health concerns. Further, these effects can persist across generations within the body (genetically ‘passing down’ trauma from grandparent to parent to grandchild), in interactions with young children (trauma histories can make it difficult to parent), and in the societal impacts of historical trauma (cumulative group trauma that persists across generations).

Despite all this, we also know that children are resilient. With proper supports, they can thrive in even the darkest of circumstances. This is where we as providers come in. We can:

• Be the voice for these young children who cannot make their own voices heard. Consider these activist groups.

• Prepare ourselves and our systems to help these children. Consider trauma-focused evidenced based treatments such as Child Parent Psychotherapy (CPP) and Trauma-focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy to treat symptoms associated with traumatic experiences. Look to court programs like Minnesota’s Infant Court and Michigan’s Baby Court, where judges and other legal personnel have been trained in infant mental health so that their decision-making processes are informed by developmental science.

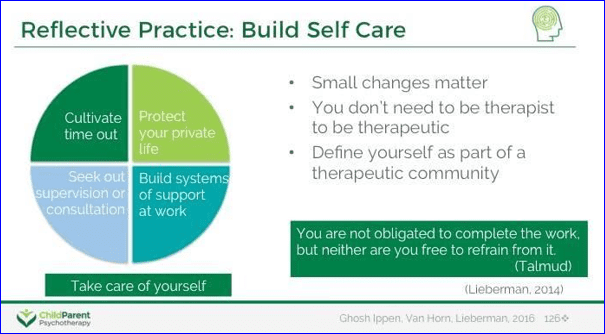

• Be reflective, practice self-care and to respond in ways that minimize our own secondary traumatic stress or compassion fatigue. In this work and amid all the news stories, advocacy pleas and personal stories, we as providers may find ourselves overwhelmed. During these times, it is important for us to ‘secure our own oxygen masks’ first in order to help more children and families. Consider the actions presented in the model below:

Visit these resources to increase your understanding of the science, trauma treatment resources, and ideas for self-care.

News articles:

• How the toxic stress of family separation can harm a child. (2018 June 18). PBS. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/health/how-the-toxic-stress-of-family-separation-can-harm-a-child

• Lussenhop, J. (2018, June 19). The health impact of separating migrant children from parents. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-44528900

- Rosenblum, K., & Walsh, T. (2018, June 18). Military families can teach us about the cost of family separations. The Hill. http://thehill.com/opinion/immigration/392831-military-families-can-teach-us-about-the-cost-of-family-separations

Trauma resources:

• Center on the Developing Child, Harvard University. (n.d.). Toxic Stress. https://developingchild.harvard.edu/science/key-concepts/toxic-stress/

• Looking At the Impact of Family Separation through the Lens of Military Parents and Kids. (2018, July 03). https://www.wpr.org/looking-impact-family-separation-through-lens-military-parents-and-kids

• National Child Traumatic Stress Network. (n.d.). Learn: Childhood Traumatic Grief. https://learn.nctsn.org/course/index.php?categoryid=20

• Society for Research in Child Development. (2018, June 28). The Science of Childhood Trauma and Family Separation: A Discussion of Short- and Long-Term Effects. https://youtu.be/9-34LJoM1HY

Self-Care resources:

• Secondary Traumatic Stress: A Fact Sheet for Child-Serving Professionals. (2011). The National Child Traumatic Stress Network. [Fact Sheet]. https://www.nctsn.org/resources/secondary-traumatic-stress-fact-sheet-child-serving-professionals

• Self-Care for Providers. (2016, June 20). Center for Pediatric Traumatic Stress. https://healthcaretoolbox.org/self-care-for-providers.html

• Smith, J.A. (2014, August 6). How to Foster Empathy for Immigrants. Greater Good Science Center, UC Berkeley. https://greatergood.berkeley.edu/article/item/how_to_foster_empathy_immigrants

………………………………

Dr. Katherine (Katie) Lingras is the University of Minnesota Extension Child Youth & Family Consortium’s 2018 Scholar in Residence. Dr. Lingras serves on the faculty and co-directs the Early Childhood Mental Program in the UMN Department of Psychiatry. She specializes in social-emotional development in early and middle childhood, with an emphasis on children on children who experience traumatic events.

Dr. Katherine (Katie) Lingras is the University of Minnesota Extension Child Youth & Family Consortium’s 2018 Scholar in Residence. Dr. Lingras serves on the faculty and co-directs the Early Childhood Mental Program in the UMN Department of Psychiatry. She specializes in social-emotional development in early and middle childhood, with an emphasis on children on children who experience traumatic events.