Blog post 3 of 5 in the series, “Military Family Readiness During and After COVID-19“

by Karen Shirer, Ph.D.

Parents with children along with medical care providers, retail employees, and other frontline workers have carried a larger share of the hardships and burdens caused by the coronavirus pandemic. Military families have also shared these burdens. As vaccinations reach critical mass and recovery continues, this is a good time to look at what we can learn from the pandemic in supporting military families with children in future disasters, including pandemics.

In the OneOp Academy online course, Supporting Parents and Children Through Hazards and Disasters, Dr. Sara Johnson describes the effects of stress, especially toxic stress, on children’s development and growth in the context of COVID-19 as a tree growing in unfavorable conditions.

Freepik.com

She noted that children adapt to high-stress environments much as the bent tree shown in the photo. These adaptations often are exhibited as conduct problems and other disruptive behaviors.

Importantly, Dr. Johnson points out that these children are not irreparably harmed but adaptive to their environment just as we are as adults. We, too, could feel like this tree growing in barren soil, bent from the wind when we experienced the stressors of COVID-19.

energy.gov

Farmers have planted windbreaks of trees to protect their homes and fields for many generations. Dr. Johnson describes the need to plant windbreaks or living snow fences to protect children from the effects of toxic stress. These windbreaks are steps that parents, caregivers, and family-serving professionals can take to both reduce risks and build protective factors. We’ll learn more about these strategies in this blog post.

This third blog post takes a deeper dive into the previous two blog posts in the series Military Family Readiness During and After COVID-19. We will expand our understanding of acute and chronic stress by focusing on the risks of toxic stress during disasters. Topics in this blog post include:

-

- A brief recap of the themes covered in the first two posts

- A closer look at the impact of the pandemic on military families with children, adding to our understanding of stress caused by the pandemic and other disasters

- Best practices and research-informed strategies that Military Families Services Providers (MFSP) can use to support families with children

- An introduction to blog post four on how COVID-19 has changed MFSP’s work with military families

This blog post draws on information from the Supporting Parents and Children Through Hazards and Disasters online course. This course was part of the Military Family Readiness Academy (MFRA) webinar series on Hazard and Disaster Response Foundations. You can access the course here.

Military Family Readiness During and After COVID-19: Recap of blog posts one and two

Most of us recall when Covid-19 became a pandemic in early 2020 and watched as the pandemic spread across the globe. A great deal has transpired since that time. We find ourselves now in the recovery phase of the pandemic!

In the US, we have effective vaccines and better treatments for COVID-19 and some of its emerging variants. Governments are lifting requirements for physical distancing and face coverings. Hopefully, we will find ourselves on the other side of this particular pandemic by the end of 2021.

But, we will likely see more pandemics and other disasters and hazards in the future due to changes in global weather patterns. There are many lessons we can learn from our pandemic experiences to better ensure military family readiness as we encounter new disasters.

Beginning in Fall 2020, the OneOp Military Family Readiness Academy (MFRA) offered a webinar series, Disaster and Hazard Readiness Foundations. The 2020-2021 MFRA focused on preparing MFSPs with the skills and resources to manage disasters and hazards within their professional fields. This blog series, titled Military Family Readiness During and After COVID-19, builds on the MFRA.

The series focuses on how acute family stress caused by COVID-19 impacted military family readiness. If unaddressed, acute stress contributes to chronic stress as well as mental and physical health challenges for military family members.

Each blog post has and will describe best practices and strategies for addressing family stress and directs you to additional resources. The first blog post described the reasons why COVID-19 is considered a disaster, an overview of acute stress and the impact of acute stress on military families during this disaster.

The second blog post took an in-depth look at an all-hazards approach to disaster preparedness in order to manage acute stress. A family resilience framework for working with military families was presented, including best practices for MFSPs for preventing and reducing acute and chronic stress in military families.

Recovery from the pandemic will likely be an uncertain journey with unexpected twists and turns. Nancy Beers, during one MFRA session, describes the recovery phase of a disaster as a “long haul.” People often face unforeseen circumstances, can become disillusioned, and may experience financial problems. This is when acute stress can morph into chronic stress and mental health concerns.

Next, we will examine the recovery needs of parents and children as the pandemic winds down in order to ensure military family readiness.

Recovery needs of parents and children due to the pandemic

Each military family’s pandemic recovery journey will be unique, based on a number of factors just as their experiences during the pandemic were unique based on their strengths and vulnerabilities. COVID-19 upended almost every part of everyone’s family life but families with children, including military families, experienced the most stress.

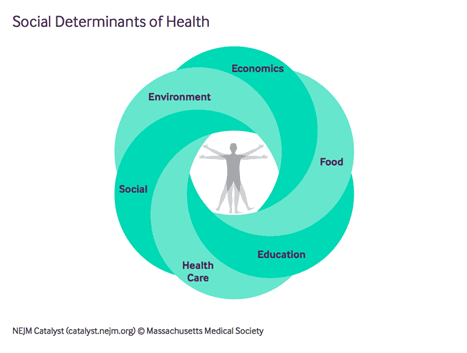

Dr. Sara Johnson, in Supporting Parents and Children Through Hazards and Disasters, speaks about how COVID-19 shaped families due to the stressors they experienced and their pre-existing vulnerability to stress’ effects. To better understand the differences in families’ responses, she used the social determinants of health (SDOH) to show how families with children were disproportionately impacted by the pandemic.

The drawing below depicts the six areas that impact an individual’s and a family’s health, and the stressors they experience. The World Health Organization defines them as “the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age.” Dr. Johnson described them as the “building blocks” of family and child well-being and health.

NEJM, 2017

Some SDOHs like the economy, the political and social environment, and culture are intangible factors that influence health. Other factors that impact health stem from “place-based” conditions such as access to health care and education, environmental toxins, neighborhood design, and access to healthy food (NEJM, 2017). These SDOHs determine one’s income, education, job, gender inequity, racial discrimination, exposure to crime and violence, and access to safe drinking water, to name a few.

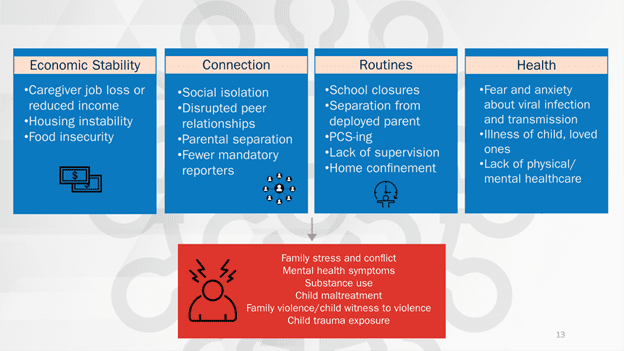

The table below shows four areas (the blue boxes) in which the pandemic disrupted the lives of military families with children — economic instability, loss of connection with others, change in family life routines, and physical and mental health concerns. These disruptions led to increases in family stress and conflict, mental health concerns, substance misuse, child abuse and neglect, family violence, and exposure to trauma (the red box).

Supporting Parents and Children Through Hazards and Disasters, OneOp webinar

Dr. Johnson cited a report from Child Trends to show that these disruptive impacts were not equally felt among all families with children. She highlighted how Hispanic and Black households with children experienced three or more hardships, at a greater rate than Asian and White households with children.

Since a larger proportion of the military population are Black and Latino than the civilian population, these hardships have also been felt by military families with children. Keep in mind these impacts are due to inequities caused by the social determinants of health. For example, those service members who are younger, at lower pay grades and with children likely experienced greater stress during the pandemic.

Toxic Stress: A result of these differences in COVID impacts

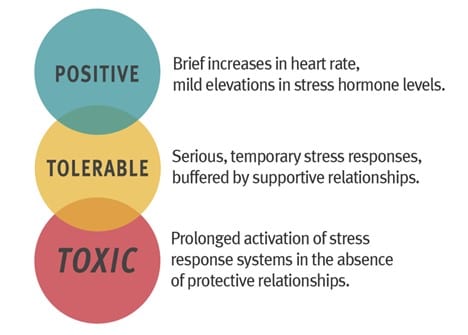

All stress is not alike as we learned in blog post one. Adding to our understanding of family stress, Dr. Johnson introduces a stress framework that includes these types of stress:

Harvard Center on the Developing Child

Tolerable stress, like acute stress, includes those serious, but temporary, responses to stress. The key to addressing this kind of stress is providing military families with supportive relationships with others, including MFSPs. We described in detail in blog post two what these supportive relationships look like in practice.

However, tolerable stress becomes toxic when family members’ stress response systems are over-activated over a long period of time. This long over-activation often results from multiple hardships typically due to disparities in the SDOHs.

The science and biology of stress in our bodies plays out when stress goes unaddressed. Consider the impact of making a permanent change of station or experiencing deployment during the COVID-19 pandemic may have had on a military family. They become more vulnerable to the effects.

Both acute and toxic stress shape parents’ and children’s behavior. These changes are called adaptations to what is occurring in the family environment. For example, Dr. Johnson describes how to conduct problems increased for many children during the pandemic as a result of family stress.

Often children’s misbehavior results from a change in or lack of family routines, which occurred during the pandemic, moving one’s family to a new community or during deployment. For our work with military families with children, these family routines are a key leverage point for addressing acute stress and the first step toward a more protective environment for children within the family.

In the next section, additional strategies and best practices will be highlighted for working with military families.

Strategies for Ensuring Resilience

The bent tree photo we began this blog post with represents what happens when protective and supportive relationships are not present and/or the military family is faced with too many hardships at one time. The family adapts to this inhospitable environment when overloaded with challenges, becoming vulnerable to the adverse effects of stress.

Despite multiple hardships, many opportunities remain for strengthening family resilience and supporting healthy child development. The live wind block photo illustrates the positive contribution of supportive and protective relationships. Service providers, like MFSPs, can provide this protection by serving as living wind blocks that enhance military family readiness.

Blog post two highlighted a number of strategies and best practices for preparing yourself to plan for and respond to the acute stress experienced by military families during disasters and hazards. You want to obtain the proper training before disaster strikes and recognize your own need for self-care while responding to and recovering from disaster. Another very important practice is to reunite military families with their support systems including family members, using technology, if necessary.

Dr. Johnson also provides these areas for applying the science of stress to our work with military families:

-

-

- Recognize the behavioral adaptations that increase family conflict and child discipline problems. These adaptations include signs of family stress and conflict, mental health symptoms, domestic violence and children witnessing it, and exposure of children to trauma.

- Use a trauma-informed lens in your own practice and help parents understand the impact of trauma on their children. Coach parents on how to be responsive with their children. Help them understand their own adaptive behaviors and their families. Learn more about a trauma-informed lens and toxic stress here.

- Plant many wind blocks around military families with children that buffer and protect them from toxic stress! As described, family rules and rituals and responsive parenting practice are two key areas on which we can work with military families.

-

Beth Meeks who followed Dr. Johnson’s presentation helped to expand our understanding of domestic violence (DV) prevention during disasters and described DV providers’ experiences during the pandemic. She also provided valuable information on how to prepare for and adapt service delivery during disasters. Here are several key points gleaned from her presentation:

-

- Remember that as we adapt to a changing climate, weather-related disasters will be more frequent, severe, and longer. Recovery will also take longer; if it was three months before, it’ll take 18 months now. She predicted that COVID-19 recovery will take longer than expected.

- Plan for future disasters by considering possible scenarios for responding and recovery. She advised that we determine multiple options and scenarios because there are usually more failures of normal standard procedures than we expect during disasters.

- Consider multiple and different locations for delivering services to military families. For example, she spoke of providers who used parks, laundromats and restaurants, like Waffle House, that typically have opened for business first after a disaster. Every community has locations of this nature; find them before disaster strikes.

- Recognize that technology use for service delivery is necessary and has been accelerated by younger generations and COVID-19. Ms. Meeks found that the availability of tech-based services was particularly beneficial to rural communities.

Beth Meeks has much more to say specifically about domestic violences. She describes COVID’s impact on violence and conflict in families, and more information on how domestic violence advocates changed their approach to adapt to the pandemic. Check it out here.

Key Takeaways

Most US families with children experienced stress and hardship during the pandemic. But Latino and Black families and those with limited resources, including military families, were more vulnerable to hardships.

Social Determinants of Health (SDOH) help explain why some families with children experienced hardships and others did not. Those experiencing disparities in health care, education, income, and other areas were more vulnerable to hardships.

Acute or tolerable stress from families’ pandemic experience led to toxic or chronic stress for some of those families with more vulnerabilities due to SDOH.

MFSPs have an active role to play in supporting and protecting military families who experience these vulnerabilities. They can learn to recognize the behaviors that indicate a family is experiencing acute or toxic stress. They also can use a trauma-informed lens to support these military families.

In addition to resources already cited in the blog post, you can find additional information at the following links:

Go Beyond the Webinar blog post—summary of the Supporting Parents and Children Through Hazards and Disasters course.

Continuing the Conversation blog post—brief summary of MFLN’s webinar Sesame Street and You: Caring for each other during COVID-19 and other emergencies

What are ACES? How do they relate to toxic stress? Center for the Developing Child, Harvard University.

A Guide to COVID-19 and Early Childhood Development, Center for the Developing Child, Harvard University.

The last blog post in this series will focus on the professionals who served military families during the pandemic. Their experiences, lessons learned and best practices will be described and applied to planning for and responding to future disasters and hazards.

Call to action

-

- Watch for the next blog post in this series — Looking to the Future after the Pandemic: Where Do We Go From Here?

- Check out the sources used in this blog post—they are all hyperlinked within the blog post and listed below.

- Review the courses and resources offered by the MFRA.

- Connect with military families that you serve to learn more about their experiences with the pandemic and get suggestions of what would be helpful to them currently.

- Share this blog post with your colleagues.

*Note: All 2020-2021 Military Family Readiness MFRA webinars on Disaster and Hazard Readiness have been made into courses and can be accessed here.

Karen Shirer is a member of OneOp Family Transitions Team and previously the Associate Dean with the University of Minnesota, Extension Center for Family Development. Karen is also the parent of two adult daughters, a grandmother, a spouse, and a cancer survivor.

References and Sources

C-CHANGE. (N.d.). Coronavirus and climate change. Harvard University T. H. Chan School of Public Health.

Military Family Research Academy. (2021). Preparing for Disaster During A Pandemic. Military Family Learning Network

Military Family Research Academy. (2021). Planning for the Worst, Hoping for the Best. Military Family Learning Network.

Military Family Research Academy. (2021). Supporting Parents and Children Through Hazards and Disasters. Military Family Learning Network.

Myers-Walls. J. (2020). Family life education for families facing acute stress: Best practices and recommendations. Family Relations, 69(3), pp. 662-676. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12452

Shirer, K. (2021). Military family readiness during and after COVID-19.

Shirer, K. (2021). Revisiting the pandemic: Lessons learned for future pandemic and disaster preparedness.