By Bob Bertsch

Summary

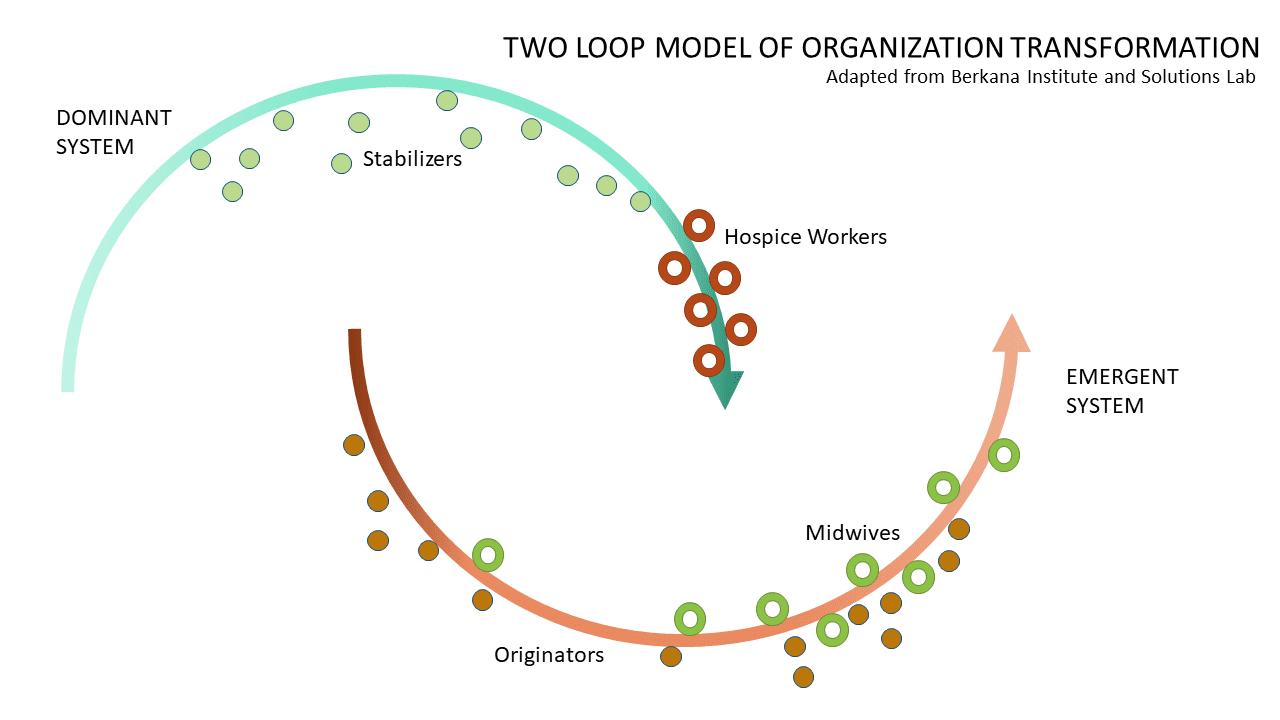

The Two Loop Theory of Organizational Change can help service providers and others working within systems in need of transformation understand the roles we can play in changing those systems. Understanding these roles helps resolve the tension between our need to help people and our desire to avoid enabling the broken system that is causing people harm.

Our food systems, in the U.S. and globally, are broken. Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack has highlighted the need to transform the U.S. food system, “When faced with grave challenges America seizes the opportunity to transform into a stronger and better form of itself. A transformed food system is part of how we as a country become more resilient in the face of these big challenges and threats.” The U.S. Department of Agriculture has set out to transform the food system“ from farm to fork, and at every stage along the supply chain.”

The World Bank has been more pointed in its assessment of the current global food systems, calling for an urgent reset of food systems that “encroach on natural habitats, pollute the planet, exacerbate rural poverty and underlie ill health and disease.” Even if we focus only on the issue of nutrition, setting aside health and the environment, the food system is falling well short. As the United Nations points out, the world produces enough food to feed everyone on the planet, but more than 800 million people are considered to be “chronically undernourished.”

These calls for “transformation” and “resets” are indications that our current food systems are in decline and new systems are emerging. We are in the process of systems change which can raise some difficult questions for service providers, Extension educators, and others working to help people in our communities.

Uprooting Broken Systems

Most of the structures and organizations that we are working with and within are rooted in the existing, broken food systems. Knowing this, we might ask ourselves whether that part of our work is propping up a system that we know to be, at the very least, ineffective.

In the book, Toxic Charity, Robert Lupton wrote about how food pantries, soup kitchens, and other organizations focused on one-way resource transfer might be making problems worse by enabling broken and unjust systems. Lupton’s book shines a light on the tension that can arise between our need to help people and our desire to avoid enabling the broken system that is causing people harm. That tension can be difficult to deal with. In our efforts to resolve the tension, we might abandon efforts to provide short-term help to people because we feel it doesn’t matter, or we might deny that the current system is broken at all.

A Model to Resolve the Tension

One way to help resolve that tension without abandonment or denial, is to understand more about systems change and the roles different people can play in that change. One model that has been particularly helpful to me is the “Two Loop Theory of Organizational Change,” developed by Meg Wheatley and Deborah Frieze and shared in their paper, “Using Emergence to Take Social Innovation to Scale.” In the article, Wheatley and Frieze suggest that in the midst of transforming themselves, organizations are simultaneously in the paradoxical process of living and dying, while a new form of organization is emerging. Within all that change, there are “stabilizers,” who try to preserve the existing organization; “originators,” who create the new structures that will lead to the new organization, “hospice workers,” who help reduce the pain and harm people are experiencing from the dying organization, and “midwives,” who are supporting originators in bringing the new organization into existence.

In this video, Deborah Frieze applies the Two Loop Theory of Organizational Change to a large-scale system, fossil fuel energy.

Seeing Our Work Through Different Lenses

Thinking about how the Two Loop Theory of Organizational Change applies to food systems change can help us see our work through different lenses. The “hospice work” of the dying food system is happening in the food banks, the school lunch programs, and the financial programs that address the ability of families to access food, reducing the harm being caused in the current system. The “midwifery” of the emerging food system is happening in food policy councils, local growers cooperatives, and other organizations that weave together the various parts of the new system.

We do not have to limit the view of our work as either propping up a broken system or actively fighting for change. Systems change is complex and nuanced, and our work within it can be, as well.