Written by: Bob Bertsch

Many resources for building our individual resilience focus on having better control of our thoughts, changing our outlook, and practicing self-care. The focus on these internal factors in our resilience makes sense. We tend to focus on the things we think we can control, but we shouldn’t ignore the interconnected, external factors that contribute to our resilience and the resilience of those we work with.

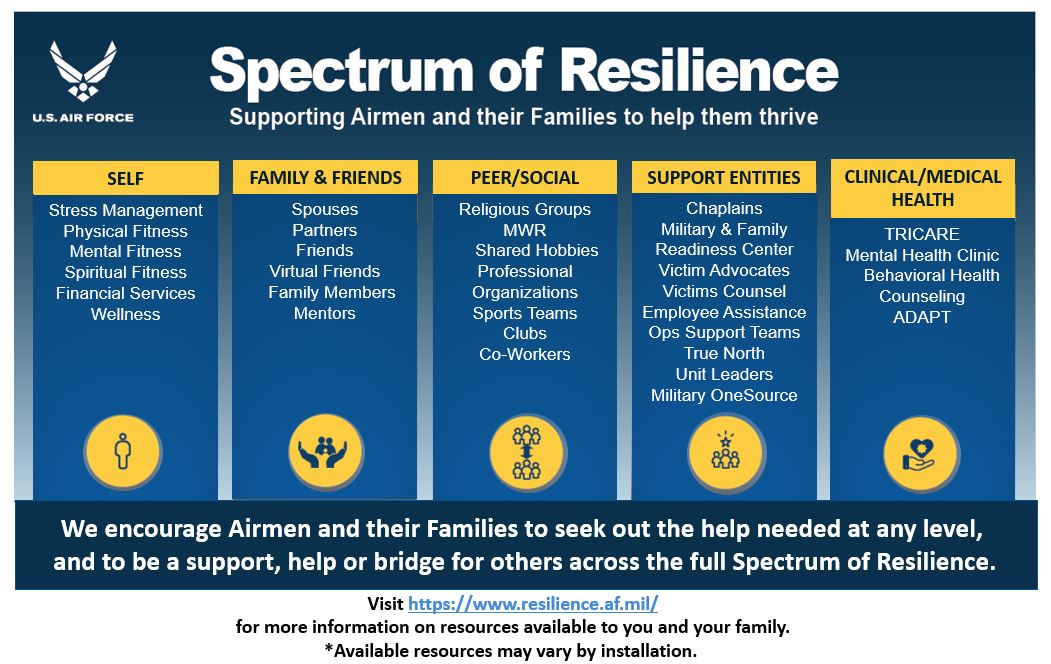

Spectrum of Resilience

The U.S. Air Force’s “Spectrum of Resilience” model emphasizes supportive connections with family, friends, peers, and service providers in helping airmen and their families thrive.

The model outlines five levels that can provide support for airmen and gives examples for each:

- Self, e.g. stress management, physical fitness, mental fitness, spiritual fitness, financial services, and wellness.

- Family and friends, e.g. spouses, partners, friends, virtual friends, family members, and mentors.

- Peer/Social, e.g. religious groups, Morale Welfare and Recreation, shared hobbies, professional organizations, sports teams, clubs, and co-workers.

- Support Entities, e.g. chaplains, Military & Family Readiness Center, Victim Advocates, Victims Counsel, employee assistance, ops support teams, True North, unit leaders, Military OneSource.

- Clinical/Medical Health, e.g. TRICARE, mental health clinic, behavioral health, counseling, ADAPT.

Airmen and their families are encouraged to seek the help they need and “to be a support, help or bridge across the full Spectrum of Resilience” (Resilience, n.d.).

Resilience as an Interconnected Process

With its focus on relationships, the Spectrum of Resilience provides a model for one individual’s network of support. Still, it can also be viewed from the perspective of other individuals represented in the model. We can put a spouse, mentor, friend, co-worker, or service provider in the role of “Self” and a new network of support emerges, one intertwined with the network centered on the original individual. These interconnected networks make up a system of support that has the potential to positively impact not only the resilience of individuals and families but also the resilience of communities.

When we view individuals as part of a network of interconnected relationships, we can see resilience isn’t “randomly distributed among individuals in a society or community, but occurs in groups of people located in a web of meaningful relationships” (Kirmayer, et al. 2009. p. 72). Individuals, families, small groups, communities, and the environment are interconnected, and factors from each contribute to the process of resilience.

Putting It Into Practice

Effective efforts to improve resilience and readiness should go beyond individual, internal factors to address the network of relationships at all levels of the Spectrum of Resilience. Michael Ungar (2011) suggests our efforts go even further to help build the formal and informal community capacity that promotes individual, family, and community resilience.

Here are a couple of things to try:

- Engage with multiple service providers and informal supports to work on increasing capacity. Ungar writes that services should be coordinated, continuous (sustained over time and accessible as needed), and co-located (multiple services accessible at a single location).

- Connect with people working on the natural and built environment aspects of community and installation resilience. The availability of affordable housing, transportation, education, and child care are just as integral to resilience as stress management and social support. Integrating our efforts supports resilience as a process between individuals, families, and communities.

References

Kirmayer, L. J., Sehdev, M., Whitley, R., Dandeneau, S. F., & Isaac, C. (2009). Community Resilience: Models, Metaphors and Measures. International Journal of Indigenous Health, 5(1), Article 1.

Resilience. (n.d.). Retrieved November 21, 2023, from https://www.resilience.af.mil/Resilience/

Ungar, M. (2011). Community resilience for youth and families: Facilitative physical and social capital in contexts of adversity. Children and Youth Services Review, 33(9), 1742–1748. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2011.04.027