Written by: Kristen Jowers, M.S., and Nichole Huff, Ph.D, CFLE

Shame is a powerful and painful emotion that arises from a perceived sense of being flawed, inadequate, or not belonging (Brown, 2006). Shame is different from embarrassment or guilt, which are typically evoked from a specific event. When someone fails to meet an expectation, they may feel guilt or embarrassment and think things like, “I could have done better.” Conversely, shame is more intensely connected to one’s sense of self, so instead of guilt or embarrassment saying “I did something wrong,” shame says, “I am wrong” or “I am bad.” Without intervention, shame can grow or bleed into other areas of a service member’s or spouse’s life, including their finances.

There are a number of situations with money that may evoke feelings of shame including bankruptcy, gambling, having debt, substance use, or food insecurity. Feeling ashamed may indicate that the person expects to be rejected just on the basis of who they are. Shame is an important concept for service providers to identify because it can impact financial behavior, as well as if or how a service member or military family shows up in your office.

Shame and Financial Disengagement

Understanding shame and its role in financial disengagement is useful for providers in assessing the degree to which a service member is participating in their economic life. Research by Gladstone et al. (2021) illustrates a strong relationship between financial shame and the urge to withdraw from financial information. Financial withdrawal could look like not checking bank statements, avoiding opening a bill, forwarding calls from the bank or bill collections, and hiding money worries from friends and family.

Financial Shame Cycle

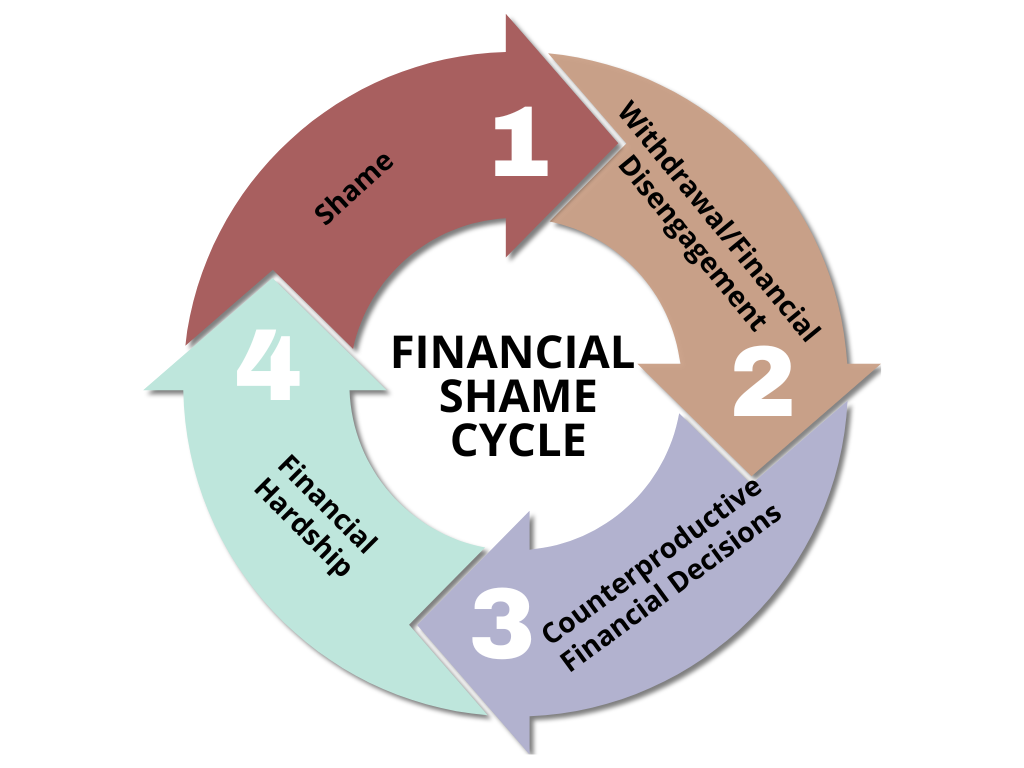

Financial disengagement is likely to lead to counterproductive financial decisions. Examples of counterproductive financial behaviors include missing payments, not keeping an updated spending plan worksheet, hiding the problem, and accruing additional debt. Shame can also contribute to money-secretive behaviors and financial infidelity. These counterproductive financial decisions can perpetuate a vicious cycle between shame and financial hardship. According to Gladstone et al (2021), the financial shame cycle illustrates how shame-induced withdrawal increases counterproductive financial decisions and exacerbates financial hardship.

Graph 1: The Financial Shame Cycle describes the recursive nature of the relationship between shame, withdrawal/financial disengagement, counterproductive financial decisions, and financial hardship.

Managing finances requires active engagement and avoidance makes things more challenging. Invite conversations around experiences of shame to encourage service members to “approach” rather than “avoid.” Identify ways to break the cycle in part two of the shame blog series.

References

Brown, B. (2006). Shame resilience theory: A grounded theory on women and shame. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Social Services, 87(1), 43–52. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1606/1044-3894.3483

Gladstone J. J., Jachimowicz J. M., Greenberg A. E., Galinsky A. D. (2021). Financial shame spirals: How shame intensifies financial hardship. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 167, 42–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2021.06.002

Adobe Stock/mirzamlk