Blog post 4 of 5 in the series, “Military Family Readiness During and After COVID-19“

by Karen Shirer, Ph.D.

Resilience is often described as bouncing back from difficult experiences or events. Sometimes, though, events and experiences become overwhelming and our efforts fall short in recovering our “bounce.” When you think about your experiences during the pandemic and now recovery from the pandemic how would you describe your resilience — still bouncing or going splat on the ground?

Many Military Family Service Providers (MFSP) discovered, like most family service providers, that the pandemic almost instantly changed their work and family lives. They found that these unexpected developments highlighted issues with the systems within which they live and work. From front-line workers to program administrators in communities and organizations on and off a military base, MFSPs experienced the stress from the pandemic’s unexpected disruptions and changes.

MFSPs, like our civilian colleagues, also faced other crises and disruptions during the pandemic. Some were personal like an unemployed partner or home schooling and others were work related like going to remote working. Plus there were larger social and racial justice protests and unrest across the political spectrum during the pandemic that created more stress. These other crises also have impacted those we serve and our collaborators, and the communities in which we live.

The blog series, Military Family Readiness During and After COVID-19, curated information found in online courses from the OneOp 2020-2021 Military Family Readiness Academy (MFRA) on Disaster and Hazard Readiness. Each blog post in this series describes military families’ experiences with stress and resilience during and now in recovery from the pandemic. Please be sure to check out all the MFRA courses here.

The blog series’ goal is to better foster recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic for military families and those who serve them with a focus on resilience and stress. The final two blog posts shift to MFSPs’ experience of and their recovery from the pandemic. Just as military families experienced both the stress and resilience associated with COVID-19, so have MFSPs.

We examine the challenges and the opportunities that MFSPs encountered during the pandemic and how they adapted through the lenses of resilience and stress. Relevant information was drawn from the MFRA course, Surviving the 2020 Pandemic: Supporting EI/ECSE Communities.

Strengthening our resilience for future crises and disasters as well as fostering our recovery from the current challenges will be explored. The pandemic’s challenges for MFSPs are highlighted in a case example of the experiences of one group of MFSP-related professionals, early intervention and early childhood care (EI/ECSE),

A case example of the pandemic’s impact: Early childhood, child care and early intervention

Early intervention, early childhood care and special education workforce (EI/ECSE) was one of many workforces deeply impacted by COVID-19. The MFRA course, Surviving the 2020 Pandemic: Supporting EI/ECSE Communities, features a panel of three experts in the field of child development, special education and early intervention. Here are a few of the practical challenges that they discovered at the beginning and during the pandemic:

Concern for personal and family safety. At the pandemic’s beginning, the primary focus for most EI/ECSE professionals was on one’s own safety and of their families. So much was unknown about the pandemic resulting in fear and great uncertainty.

Concern for front-line workers’ safety and well-being. Administrators and supervisors were concerned about the safety of their front-line workers, including home visitors and child care professionals. They began to look for ways to support them through the changes and transitions that would need to be made in their work.

Immediate shift in how services were delivered. When COVID stay-at-home orders were implemented, programs and organizations quickly looked for alternatives to face-to-face delivery, which is the norm in the field. Program leaders and managers in home visiting or group programs needed to shift existing work plans to formulate a new plan that enabled staff to work remotely and virtually with families. Many child care EI/ECSE closed for the mandated period of time.

Remote workers faced multiple demands. Many employees were also parents of children in school who were under the stay-at-home order. They needed support and guidance on how to manage both their schedules and the technology required for remote work. Many employees needed technology skills, Internet access and hardware/software in order to virtually work with families.

Communication was and continues to be very important. Clear, frequent and transparent communication strategies were needed with their employees, especially front-line professionals. Every conversation with employees soon began with exploring the question: “How are you?” Front-line professionals also found creative and new ways to engage with their families.

Feelings of trauma. As the pandemic continued, the panelists found that most employees as well as themselves were experiencing feelings of trauma. All three panelists agreed that worker’s mental health will be an important area to address during recovery from the pandemic.

Importance of reflection and analysis. Despite the busyness and chaos, the panel’s experts identified the importance of reflecting and analyzing what was working and what wasn’t early in the pandemic. This has remained a need throughout the pandemic and into recovery.

Families served by EI/ECSE experienced multiple pandemic-related vulnerabilities. EI/ECSE professionals learned early on that many of their families experienced multiple challenges. Many didn’t have the technology to support virtual home visiting or for their children’s remote schooling. Families tended to be lower income and/or had lost their jobs. Health, educational, and economic disparities were exaggerated by the pandemic. As a result, EI/ECSE professionals found families unavailable for programs and often worried about the families’ well-being.

The panelists’ experiences tell a story about how this one group of providers serving military families, EI/ECSE, coped with the pandemic’s impacts for their organizations, employees, their families and children, and communities. In the course, they go on to describe the more unique challenges they faced and how they made the necessary adjustments and changes to how they did their work.

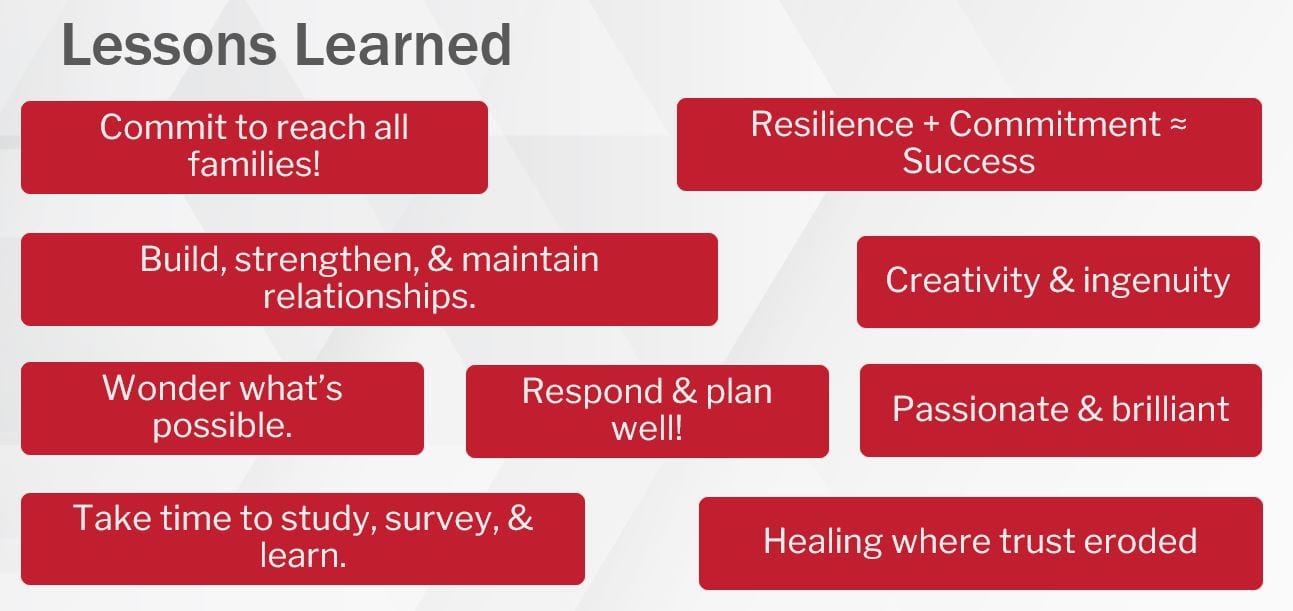

At the end of the course discussion, each panelist was asked to share the important lessons that they learned during the pandemic about their work. Two lessons emerged from among many.

First, professionals and families demonstrated resilience, flexibility and ingenuity in building relationships within the constraints of COVID-19. Relationships are at the heart of early intervention and COVID disrupted the primary way those relationships were fostered — in person. People seemed to surprise themselves on what they were able to achieve. All three panelists celebrated the strength and resilience they saw throughout the pandemic.

The second lesson that arose during the pandemic in EI/ECSE work related to heightened need for evaluation and research. COVID-19 left a lasting impact on EI/ECSE professionals and the families and children with whom they serve. Research and evaluation are needed to determine the most appropriate and effective next steps for recovery and for shaping their future well-being.

Many of the pandemic experiences of the EI/ECSE field likely resonated with you; likely your organization, those you serve and you personally were impacted in similar ways. In the next section, we will look at the implications of this case example for all MFSPs and organizations using both a stress and resilience lens.

The COVID pandemic’s uncertainty, disruption and need for rapid adaptation led to stress and trauma

Another challenge highlighted throughout the EI/ECSE panel discussion focuses on the trauma sustained by professionals, families and children from their pandemic experiences. This trauma is likely very similar to the toxic stress described in blog post three. All three panelists agreed that planning, time and effort need to be devoted to trauma recovery efforts for EI/ESCE professionals and the families with which they work.

Dr. Kathleen Allen*, a leadership consultant and author of Leading from the Roots, noted in a recent blog post that the organizations in which we work also need to recover and heal from the trauma of COVID-19. This organizational trauma came from the systems that failed during the pandemic and the need to rapidly adapt to multiple disruptions. The MFRA course highlighted that EI/ESCE organizations experienced these system failures and the resulting trauma, too.

An EI/ECSE example was not having prepared for remote delivery of programs and services, even though it had been an important need before the pandemic. They were forced to quickly adapt a tele-health approach with children and families. These adaptations needed to address privacy requirements, assessment and upgrading of professionals’ technology skills, and families’ access to technology. This one disruption alone was accompanied by many others for families, professionals and organizations.

Dr. Allen states even the “familiar” changes made during the pandemic led to some level of trauma “because the new routines were not part of our individual and organizational habits.” She goes on to say that these changes “rippled” across every aspect of our lives, especially for parents who found themselves working remotely and schooling their children at home. And Dr. Allen poses the question “How do we begin our own healing?”

A first step in healing and recovery from the pandemic or any other disaster for your colleagues and yourself is to understand the effects of stress. In blog posts one through three, we found that acute stress and toxic or chronic stress impacted military families due to the pandemic. Like military families and EI/ECSE professionals, we were not immune to the pandemic’s stressors and related trauma. Stress or trauma may have been or continues to be a problem for your colleagues or you.

Acute stress, the most common type of stress, is defined as “the sudden or unexpected onset of moderate or severe discomfort and or disequilibrium and feelings of inadequacy” (Myers-Walls, 2020). EC/ECSE professionals found themselves feeling acute stress due to the seemingly quick onset of the pandemic and the sudden rapid adaptations they needed to make in their professional and family lives.

Acute stress leads us to feel overwhelmed, uncomfortable and uncertain, due to a belief that we lack the tangible and intangible resources to address the challenges (Myers-Walls, 2020. EI/ECSE professionals were forced to rapidly adapt to remote services in a field that relies heavily on face-to-face interaction. Many discovered they lacked the technology skills and tools to effectively respond.

Acute stress In small doses energizes us; we often call this resilience. But too much stress leads to toxic/chronic stress and mental health challenges when it goes beyond our tangible and intangible resources (APA, 2019, Myers-Walls, 2020; Pfefferbaum & North, 2020). The pandemic’s slow-burn nature has created chronic and toxic stress for many military family members and many of us.

Toxic or chronic stress puts one at increased risk for health problems like anxiety, depression, digestive problems, heart disease, sleep disorders, unhealthy weight changes, and memory problems (Mayo Clinic, 2019). My daughter has a favorite saying when she describes her weight gain over the last year — “It’s my COVID-15.” We want to be attentive to these risks and take steps to counter them as we recover from the pandemic.

Recently, many media articles have focused on mental health and recovery from the pandemic. You likely have seen some of them along with stories of resilience during the pandemic. They highlight many strategies for helping us, our colleagues and others to recover from acute and toxic/chronic stress.

You will also find many research-based strategies in the Revisiting the Pandemic: Lessons Learned for Future Pandemic and Disaster Preparedness and Managing the Ups and Downs of the Pandemic: What We’ve Learned about Supporting Military Families and Parents. Below is a brief recap of strategies, which are described in more detail in the blog posts.

Take an all-hazards approach for addressing future pandemics and disasters. This approach promotes planning for multiple disasters at one time, like a hurricane and a pandemic.

Connect with military families and your organization using the perspectives of individual resilience, family resilience and community resilience. These perspectives encourage us to develop positive and supportive relationships with family members and colleagues, to work with the family as a system, and to engage the community as a partner in our work. In 2019, OneOp offered a three-part webinar series on all three topics. You can access it here.

Address your own need for self-care while responding to future pandemics and disasters and while recovering from the recent pandemic and other disasters. Find a contemplative practice, like prayer or mindfulness, to help reduce and better manage stress. A recent OneOp blog post highlighted one resource on mindfulness from Military One Source.

Encourage military families to reunite with and strengthen their support systems and family relationships, including family members that they may have lost touch with or experienced conflict with during the pandemic. This need is especially critical during all disasters.

Recognize that military families have experienced family conflict and child discipline problems. These are signs of family stress and conflict, mental health symptoms, domestic violence and children who have witnessed it, and/or exposure of children to trauma. Some of us may have experienced these kinds of conflict and may need to seek professional assistance.

Use a trauma-informed lens to help military families and colleagues understand the impact of the pandemic’s trauma on them. Coach parents on how to be responsive with their children. National Child Traumatic Stress Network has a resource page dedicated to military families and veterans here. On August 31, 2021, OneOp will hold a webinar on post-traumatic pandemic stress. You can learn more about it here.

One last strategy is the one I began with: learn all you can about buffering and protecting yourself and those around you from acute and toxic stress when disaster strikes. As described in blog post three, family rules and rituals and responsive parenting practice are two key areas on which we can work with military families and in our own family lives.

Take time to review the other blogs in this series and the MFRA courses on disaster preparation. They will provide more information on the above strategies as well as other ones to prepare for future disasters.

Key Take-Aways and Conclusion

The COVID pandemic caused disruptions and uncertainties for almost every aspect of life — work, school, family life and parenting, leisure activities. Many MFSPs and others serving families experienced acute stress during the pandemic but also discovered resilience in bouncing back.

In a matter of days, we saw dramatic changes in how we conduct our work due to the need for both working remotely and our children’s home schooling. These disruptions led to rapid adaptations which further exacerbated acute stress.

The pandemic’s slow-burn nature and other factors caused some MFSPs and those military families they served to be overwhelmed by acute stress. This led to toxic or chronic stress. Recovery strategies enhance pure resilience as the pandemic winds down and prepares us for future disasters and hazards.

Many strategies and resources for recovery and to enhance resilience and recovery are available to MFSPs and military families. A number of them were outlined in this blog post.

We began this blog post with a picture of two soccer balls — one fully inflated and the other one deflated. We are like the deflated soccer ball when our resilience or capacity to bounce back are overwhelmed by stress and trauma. Hopefully, you discovered some new ideas and strategies for re-inflating and keeping your “ball” full as we recover from the COVID pandemic.

In the next blog post, we will build on all these strategies on using an asset-based recovery framework to support recovery from the pandemic. The approach helps to boost our own recovery and resilience and for military families, our organizations and our communities. Look for it in the near future.

Call to action

-

-

- Watch for the next blog post in this series — Looking to the Future of Resiliency after the Pandemic: Asset-Based Community Recovery

- Check out the sources used in this blog post—they are all hyperlinked within the blog post and the reference are listed below.

- Review the courses and resources offered by the MFRA.

- Connect with military families that you serve to learn more about their experiences with the pandemic and get suggestions of what would be helpful to them currently.

- Share this blog post with your colleagues.

-

Karen Shirer is a member of OneOp Family Transitions Team and previously the Associate Dean with the University of Minnesota, Extension Center for Family Development. Karen is also the parent of two adult daughters, a grandmother, a spouse, and a cancer survivor.

References

Allen, K. (June 17, 2021). Acupuncture for Organizations.

American Psychological Association (2019, October 25). Stress won’t go away? Maybe you are suffering from chronic stress. https://www.apa.org/topics/stress/chronic

Mayo Clinic. (2019, March 19). Chronic stress puts your health at risk. https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/stress-management/in-depth/stress/art-20046037

Myers-Walls. J. (2020). Family life education for families facing acute stress: Best practices and recommendations. Family Relations, 69(3), pp. 662-676. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12452

Pfefferbaum, B., and North, C. (2020). Mental health and the COVID-19 pandemic. New England Journal of Medicine, 383, pp. 510-512. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMp2008017