By Emily Becher and Emily Krekelberg; adapted by Sara Croymans

What is anticipatory grief?

Anticipatory grief is experiencing a sense of grief prior to a loss. Anticipatory grief can be protective, allowing someone to move through difficult emotions, and to emotionally prepare for the loss to come. In fact, some researchers use the term ‘preparedness’ as a synonym for anticipatory grief, as it is a normal and often functional part of loss when we are aware a loss is on the horizon. Stressful life events, particularly those that are threatening or traumatic, can particularly impact and worsen anticipatory grief. Anticipatory grief can cause an increased experience of ambiguous loss because we mourn something while it is still present in our lives. In some cases, the anticipated loss does not actually happen, but that doesn’t invalidate the grief that has already been experienced.

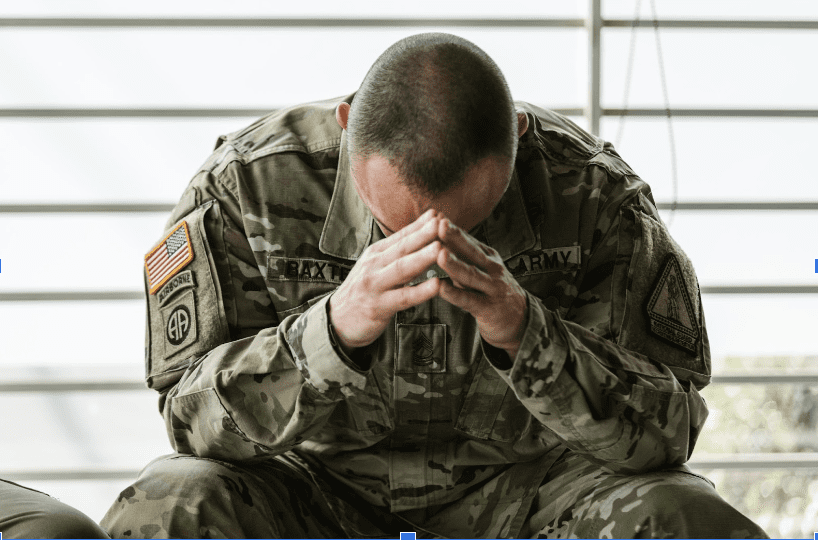

Military service members and family members may experience anticipatory grief as they prepare for a deployment, PCS (permanent change of station), or transitioning out of the military.

What can anticipatory grief feel like?

- Psychologically and emotionally preparing for a loss

- Feeling anxious or worried

- Thinking about the loss frequently

- Feelings of sadness and grief as if the loss has occurred

- Making practical decisions to prepare for the loss

- Making decisions as if the loss has already happened

- Emotionally and physically disconnecting from the person/place we anticipate losing

What can be done to prevent or reduce anticipatory grief?

Some anticipatory grief is a normal and functional part of life. However, chronic and unmanageable anticipatory grief is not helpful. As a service provider, suggest the following strategies on how to prevent or reduce anticipatory grief to the service members and families you work with.

Grieve in small doses.

Research indicates that adaptive, healthy coping involves switching back and forth between taking time to confront the loss to come and then taking the time to think about other things and to find opportunities for respite. This balancing back and forth between the two experiences (confronting and restoring) is critical to healthy coping.

Build up resources.

When confronting a loss, there are two parts: 1) Recognizing the seriousness of the loss to come and, 2) Appraising if we have the resources to cope with the loss. When we feel the loss will overpower our resources, the experience of anticipatory grief can become more intense. It is important to think about what support you have in your life and where you might have some gaps and need some help. Suggest military families tap into their networks and available resources for support.

Increase sense of control.

Often loss can make us feel out of control of our lives and can lead to an increase in anticipatory grief. It is important to find small tangible ways to feel a sense of self-efficacy and control in your life. For example, setting a very reasonable small goal for yourself and accomplishing that goal every day could be one step towards feeling a greater sense of control over your life circumstances.

Take care of yourself.

People who exercise regularly, eat nutritious meals, get enough sleep, have ways to relax and have fun, and have positive relationships with others are generally able to better cope with difficult experiences.

How can you support individuals struggling with anticipatory grief?

As a service provider, help the individual understand that what they are feeling is normal. Encourage those who are struggling with anticipatory grief to talk to a healthcare provider who can discuss their concerns and identify what the next steps might be.

Review the blog post, Grief is a Common Emotion for Military Caregivers and the podcast on Responding to Grief provided by our OneOp Military Caregiving colleagues.

Share these Military OneSource resources with the service members and military families you work with:

- Taking Care of Yourself During Times of Stress and Grief.

- Free, confidential face-to-face non-medical counseling for service members and military families

References

Coelho, A., de Brito, M., Teixeira, P., Frade, P., Barros, L., & Barbosa, A. (2020). Family Caregivers’ Anticipatory Grief: A Conceptual Framework for Understanding Its Multiple Challenges. Qualitative Health Research, 30(5), 693–703. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732319873330.

Nielsen, M. K., Neergaard, M. A., Jensen, A. B., Bro, F., & Guldin, M. B. (2016). Do we need to change our understanding of anticipatory grief in caregivers? A systematic review of caregiver studies during end-of-life caregiving and bereavement. Clinical psychology review, 44, 75-93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2016.01.002.

Schut, M. S. H. (1999). The dual process model of coping with bereavement: Rationale and description. Death studies, 23(3), 197-224. https://doi.org/10.1080/074811899201046.

Stroebe, M. S., Folkman, S., Hansson, R. O., & Schut, H. (2006). The prediction of bereavement outcome: Development of an integrative risk factor framework. Social science & medicine, 63(9), 2440-2451. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.06.012.

Sweeting, H. N., & Gilhooly, M. L. (1990). Anticipatory grief: A review. Social science & medicine, 30(10), 1073-1080. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(90)90293-2.

Emily Becher is an Applied Research and Evaluation Specialist at the University of Minnesota Extension Center for Family Development. Emily has a background in couple and family therapy and trauma-informed adult education.

Emily Becher is an Applied Research and Evaluation Specialist at the University of Minnesota Extension Center for Family Development. Emily has a background in couple and family therapy and trauma-informed adult education.

Emily Krekelberg works for University of Minnesota Extension as the Extension Educator for Farm Safety & Health. Her work focuses on grain bin safety, livestock safety, tractor safety, farmer mental health, and suicide prevention. A passion of Emily’s is weaving together the science of production agriculture with the art of building resilience.

Emily Krekelberg works for University of Minnesota Extension as the Extension Educator for Farm Safety & Health. Her work focuses on grain bin safety, livestock safety, tractor safety, farmer mental health, and suicide prevention. A passion of Emily’s is weaving together the science of production agriculture with the art of building resilience.

Sara Croymans, MEd, AFC, University of Minnesota Extension Educator, member of the OneOp Family Transitions team, military spouse, and mother.

Sara Croymans, MEd, AFC, University of Minnesota Extension Educator, member of the OneOp Family Transitions team, military spouse, and mother.

Photo source: Pexels.com/RODNAE Productions