by Tweety Yates, Ph.D.

In our recent webinar, “Strategies for Supporting Caregiver-Child Interactions That Enhance Development,” we continued to explore the use of triadic strategies. As a reminder, these strategies are used by early intervention (EI) and early childhood (EC) professionals to strengthen and enhance caregivers’ capacity to create positive, sensitive, and engaging interactions with children to support their development.

The six triadic strategies are:

Establish Dyadic Context: Create dyadic activities to increase the chances that playful interactions will occur.

Real Life Example: A social interaction game such as peek-a-boo can be used to encourage the caregiver and child to play a turn-taking game together.

Affirm Parenting Competence: Support the caregiver’s competence and confidence by warmly recognizing and expanding on their use of developmentally supportive interactions with their child or children.

Real Life Example: If the caregiver is singing a song with the child and the child is clearly enjoying the interaction, the EI/EC professional might point out how much the child is enjoying the song and interaction. The EI/EC professional may also comment on the ways the game is supporting the child’s development.

Focus Attention: Focus a caregiver’s attention on the child by commenting on or questioning something the child is doing.

Real Life Example: A caregiver is focused on a household chore and the child is trying to put a key in the lock. The EI/EC professional might say, “Sue, look what Kayley is doing! She is trying to put the key in the lock! She is really trying to figure out how the key fits in the lock. Have you seen her do that before?” By commenting, the caregiver’s attention is now focused back on the child.

Provide Developmental Information: Provide information to the caregiver about the child’s development by verbally labeling or interpreting the child’s social-emotional, cognitive, language and motor abilities as they are playing and interacting.

Real Life Example: A caregiver is playing a turn-taking game with the baby. When the caregiver stops playing the game the EI/EC professional says, “Look how she is moving her legs and arms. That is her way of communicating that she wants to do it again!”

Model: Model a strategy, idea, or skill by momentarily taking on the role of the caregiver with the child.

Real Life Example: A therapist might be demonstrating a technique for helping a child sit with support so he can have more opportunities to interact with other children at his childcare center. As soon as she demonstrates the strategy, the therapist asks the caregiver to give it a try. The word momentarily is very important here because the therapist does not want to take over the primary role of the caregiver with the child (dyad).

Suggest: Give the caregiver a specific suggestion as to what to do with the child.

Real Life Example: The EI/EC professional might say, “I wonder what would happen if you tried rolling the ball to Joey and saying, ‘My turn! Your turn, roll it back to me.’ What do you think he will do? Let’s try it and see what happens.”

The continuum across the six triadic strategies moves from establishing a dyadic context, which is very non-directive, to the more directive strategy of making a specific suggestion for a caregiver to try. It is important to remember that the further down the continuum, the more directive you are being and the more YOU are deciding what the dyad should be doing.

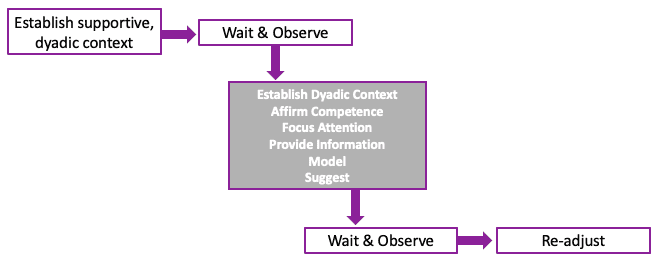

To illustrate how fluid this process is, and how it requires continual observation and decision making, many examples for applying the triadic strategies were given during the webinar. The idea is to provide just the right amount of direction and support needed for the dyad at that point in time. Too much support and direction can be intrusive and take away the caregiver’s confidence and competence. Below is a diagram that we discussed to help us decide on a strategy.

We also discussed how important routines are, including both center- and home-based routines. We know that caregivers and children are more engaged in general, and with each other, when the focus is on the child’s participation in daily routines, rather than activities that just target missing skills. When caregivers and children are engaged, intervention is more likely to be meaningful, useful, and successful.

Real Life Example: Mom says that Jack’s bedtime is hard for their family. Together, we decide to take pictures of Jack going through the steps of the bedtime routine and then put the pictures together as a book. The family will use the book at bedtime to walk Jack through the steps of the routine. In addition, the parent and home visitor go through the book to look for opportunities for Jack to practice working on his language and motor skills.

Triadic strategies were used by the home visitor in the previous example when they acknowledged Mom’s concern about bedtime. This was a great way to support her competence and confidence as well as provide developmental information related to steps in the bedtime routine (e.g., letting Jack try to hold his own toothbrush supports his motor skills).

As we ended the webinar, we thought about how small changes, such as changing our position so the caregiver is the primary interactor with the child, can have a big impact. To support EI/EC professionals in applying triadic strategies and reflecting on the small changes they might make in their own practices, this additional resource sheet was provided. Remember that triadic strategies can be used anywhere, anytime to support the competence and confidence of caregivers and children!

To view the archived version of this webinar, visit the webinar event page.