Blog post 5 of 5 in the series, “Military Family Readiness During and After COVID-19“

By Karen Shirer, Ph.D.

Courtesy Photo from the Air Force Reserve Command

In June, a team of five current and former Air Force service members had one purpose in climbing Mt. Denali, the highest peak in the United States with an elevation of 20,310 feet. Their aim was to put a spotlight on the importance of “pro-silience” or proactive resilience. Several team members had suffered mental and physical health challenges related to military service and hoped to strengthen their recovery.

The team successfully summited Mt. Denali but the climb was not without challenges and crises. They discovered that a risk management mindset and careful and thorough planning enabled them to manage these challenges. They were prepared for the unexpected and remained calm in a crisis. Back-up supplies, especially communication equipment, were essential to overcoming challenges. You can read more about their experience here.

Most of us likely won’t climb Mt. Denali to build our resilience, but other strategies remain for us to proactively strengthen it in preparation for future pandemics and disasters. In this fifth and final blog post of the Military Family Readiness During and After COVID-19 series, we examine the difference between proactive and reactive resilience and an asset-based approach that can build resilience for future disasters.

Throughout this series of blog posts, we have explored the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on military families and Military Family Service Providers (MFSPs). The pandemic’s unexpected disruptions caused acute and chronic stress for people and led to trauma for some. Each blog post highlighted evidence-informed strategies and approaches for managing stress during the pandemic and other disasters as well as our recovery needs. Additional strategies for recovery will be offered in this final blog post.

Pro-silence: What is it and how does it relate to resilience?

The word “pro-silence” can not be found in the dictionary or the research literature on resilience, but an Internet search will give several results on the topic. Instead of pro-silence, the research distinguishes between two views of resilience — the traditional view and a proactive view. The Oxford Dictionary gives two definitions of resilience reflecting the traditional view:

… the ability of people or things to recover quickly after something unpleasant, such as shock, injury, etc.”

…the ability of a substance to return to its original shape after it has been bent, stretched, or pressed.

These two definitions assume that resilience is an ability or the competence that people or systems possess to return to their original form, state, and functioning after a disruption. For example, the pandemic shocked people and caused them stress, sometimes toxic in nature. We want people to return to normalcy or their usual, typical, or expected state of being. Also called reactive resilience, traditional resilience is necessary for obtaining this return to normalcy.

Unfortunately, the pandemic exposed disparities and vulnerabilities in our systems that put many individuals and families at risk for toxic stress and trauma. Returning to the status quo is not the best approach for their recovery; more is needed. Instead, a proactive approach that takes active and intentional steps toward recovery provides a more effective approach for future resilience.

The Air Force team that climbed Mt. Denali found that the best steps for proactive resilience were planning for the climb and anticipating the risks associated with it. These two words – planning and anticipating – are key to our efforts towards proactive resilience. This same approach also needs to be applied in our pandemic recovery efforts using an all-hazards approach to planning and preparing for future pandemics and other disasters.

Over the past 40 years, many studies conducted with children, families, and communities have helped us better understand how to proactively promote their resilience. This framework of proactive resilience asserts that reducing risk factors and strengthening protective factors leads to healthy development and future well-being. Here are examples of descriptions of risk and protective factors for child welfare and substance abuse.

Figure 1. Protective Factor Approaches in Child Welfare

Many of us as professionals favor a strengths-based approach over a risk-based one when working with children, families, and communities. There are good reasons for doing so. Families often feel stigmatized when professionals focus only on their risk factors. But we can not totally ignore the disparities and inequities that were exposed by the pandemic. Many of these risk factors will require systematic changes related to public policy and program delivery, including in the military.

But a good place to begin with those with whom you work is to identify their strengths, assets, and resources, and build upon them. Both proactive and reactive resilience is required for recovery, which is a dynamic and changing process. We may find ourselves shifting between addressing risks that emerged during the pandemic and finding ways for those we serve to build their strengths for future resilience. Both views of resilience will enable us to build back better.

In the next section, we look at one approach for proactively strengthening resilience using a strengths-based approach.

Focus on Strengths First: Asset-Based Community Recovery

Just as there are two views of resilience, there are two ways that we can view our recovery from the pandemic: from a strength- and asset-based approach, or from a deficit-based approach. The challenge is to thread the needle between both frames to ensure a healthy recovery process. The best approach focuses on assets and strengths first while identifying and managing future risks at the same time.

Jessica Beckendorf and Robert Bertsch, in the Connecting with Communities in Asset-Based Disaster Recovery course, describe the Asset-based Community Recovery (ABCR) process as a “strengths-based” approach. The framework was developed by Heather Keam and Jonathon Massini during the COVID-19 pandemic. They designed it to help communities recover from COVID-19 and other disasters through better understanding what was occurring and identifying better ways to move forward.

Bertsch and Beckendorf adapted the ABCR framework to a virtual workshop for MFSPs and other military-connected family service professionals. The workshop’s purpose was to discover ways to better support military family readiness and resilience in the face of complex disasters like the pandemic. The workshop’s approach was described as a “bottom-up” one that allowed participants to share their experiences and strengths and to develop a path forward through recovery.

Workshops were conducted in February and March of 2021 and the results have been shared in the Connecting with Communities in Asset-Based Disaster Recovery course. In the workshops, participants were guided through the three key areas of the ABCR cycle—crisis, discovery, and resurgence. The process took about 2 hours and involved facilitated discussions. Figure 1 depicts the framework in graphic format and includes descriptions of each area.

These questions guided participants through the framework’s cycle and helped them to reflect upon their pandemic experiences during the workshop:

-

-

- Crisis: Do you have a story that comes of your COVID-19 experience that inspires hope?

- Discovery: Which unknown assets or strengths have come to light for you? And what happened that you do not want to lose?

- Resurgence: What did you need or wish for during the pandemic that your community or organization can provide now?

-

Participants’ stories from the workshop discussions were sorted into the theme areas shown in Figure 2. MFSPs’ stories played a key role in designing a more tailored recovery process from the pandemic and a path forward to prepare for the next disaster.

Figure 2. Themes that Emerged, Connecting Communities in Asset-Based Community Recovery, page 11.

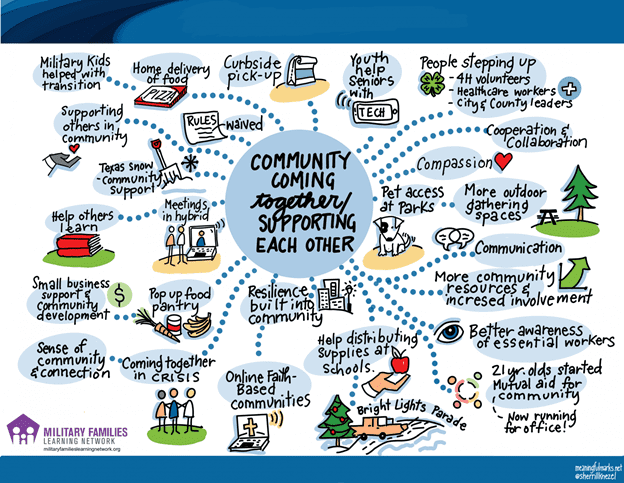

Figure 3 depicts the stories from the theme area on the community coming together and supporting each other. These brief snippets show a rich diversity of assets and strengths that can be deployed for disaster recovery in the future. A resource booklet based on the workshop provides similar graphic presentations for the other theme areas as well as ideas and strategies for recovery.

Figure 3. Stories of Communities Coming Together, Connecting Communities in Asset-Based Community Recovery, page 32.

The resource booklet and the course both provide enough information for you to hold a similar process with your colleagues, the military families you serve, and/or your community. An important part of building proactive resilience is strengthening our connections with each other just as the Air Force team did when they climbed Mt. Denali. You do not need to summit Mt. Denali to proactively improve your resilience!

Key Take-Aways and Conclusions

We can take active steps to strengthen our resilience during and after a disaster, including the pandemic.

Proactive and reactive resilience are both needed for recovery. Reactive resilience is the ability to bounce back whereas proactive resilience is bouncing back better.

Proactive resilience involves taking intentional steps to plan for and to manage risk for future events and disruptions. It begins with identifying one’s assets and strengths.

An asset-based approach to recovery holds great potential for supporting resilience for future disasters and pandemics.

Many resources and ideas are available for boosting the recovery from the pandemic of military families, MFSPs, and their communities.

As I was preparing this blog post, the United States was experiencing a surge of cases and deaths from COVID-19 due to variants. Pandemics occur in ongoing waves of increasing and decreasing cases and deaths depending on the measures taken to control the disease’s spread. We will likely be experiencing recovery from this complex disaster for an extended period of time.

To close this blog series, I want to encourage you to take time to recover your personal resilience. We all have been challenged to various degrees. Recovery from the pandemic will take time and won’t happen overnight. The Connecting Communities in Asset-Based Community Recovery resource book (pp. 28-31) provides ideas and resources for investing in yourself and your recovery, and for the military families with which you work.

Call to Action

-

-

- Use the ABCR process to reflect on your pandemic experience and the strengths and assets you discovered in yourself and others around you. Page 7 of the Connecting Communities in Asset-Based Community Recovery resource book is a helpful guide for this self-discovery.

- Check out the previous blog posts in this series — Military Family Readiness During and After COVID-19

- Check out the sources used in this blog post—they are all hyperlinked within the blog post and the references are listed below.

- Review the courses and resources offered by the OneOp Military Family Readiness Academy.

- Connect with military families that you serve to learn more about their experiences with the pandemic and get suggestions of what would be helpful to them currently.

- Share this blog post with your colleagues.

-

Karen Shirer is a member of OneOp Family Transitions Team and previously the Associate Dean with the University of Minnesota, Extension Center for Family Development. Karen is also the parent of two adult daughters, a grandmother, a spouse, and a cancer survivor.

Sources used in this blog post

Beckendorf, J., Bertsch, B. & Scott, B. (2021). Connecting Communities in Asset-Based Community Recovery Resource Book. Military Family Learning Network.

Joyner, B. (2021, May 18). Denali climbers hope to highlight importance of proactive resilience. Air Force Personnel Center.

Massini, J. & Keam, H. (2020) Asset-based Community Recovery. Tamarack Institute.

Military Family Readiness Academy. (2021). Connecting with Communities in Asset-Based Disaster Recovery. Military Family Learning Network

Military Family Learning Network. (2020-2021). OneOp Military Family Readiness Academy: Disaster and Hazard Readiness.

Military Family Learning Network. (2021). Military Family Readiness During and After COVID-19.

Perkins, J. (2021, July 17). Highest risk, biggest reward: Planning for Denali. Force Personnel Center.

SAMHSA. (n.d.). Risk and Protective Factors. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Service Administration.

Shirer, K. (2021). Military Family Readiness During and After COVID-19 [5-part blog]. Military Family Learning Network.